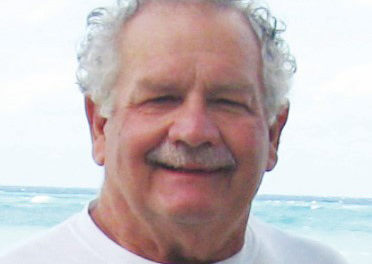

The USS Cairo in 1863.

I’ve always been a history buff. Mostly Naval history, Civil War and World War II. Therefore, our winter cruise this year was down the Mississippi River visiting various historical points of interest.

In the mid 1800s the Mississippi River was the major trade route of the country. Cattle, pork, and wheat came from the West. Raw materials and manufactured goods from the Great Lakes and Pittsburgh came down to the Mississippi via the Ohio River.

At the outset of the Civil War the Confederacy had full control of all shipping due to a string of forts built all along the river. Once New Orleans fell, the North quickly overran all these forts with the exception of Vicksburg, Mississippi.

There the fort was an integral part of the city, which was built on a 200-foot-high bluff overlooking the river. On the river side, it was defended by 129 cannons, and in the rear it was surrounded by almost impenetrable swampland. From 1861 through ‘63 the Union troops tried unsuccessfully to take the city.

River-going gunboats from the new “Brown Water” Navy could not train their guns high enough to successfully fire on the cannons mounted at the top of the bluffs, and after two years of trying to drag artillery pieces through the swamps behind the city, Generals Grant and Sherman decided to try another approach.

They realized that the “Blue Water” Navy could transport a lot of very heavy artillery quickly from point A to point B, as opposed to the Army, which could only move much smaller field artillery pieces at a much slower pace. Included in the Navy’s arsenal were a number of “mortar” boats, each carrying a single large caliber gun that would fire a shell up in an arc above the target to explode overhead raining down shrapnel on everything below. This would overcome the disadvantage of firing up at the cannons mounted on the bluff. These guns were so powerful that each time they were fired, the entire crew would have to stand on tiptoe with their mouths open and their hands over their ears to avoid being deafened by the concussion.

Therefore, Grant and Sherman got together with Admiral Farragut in New Orleans and between them, they came up with a plan where the sea going frigates and mortar boats would come upstream to attack the fort from the river while the Army under Grant and Sherman would attack from the rear.

Although it was a challenge to navigate these deep-draft, sea going ships up the winding river past snags and shifting sand bars, they met up with the Army and commenced the attack. After a few days, the city surrendered, and the whole river was under Union control. This not only allowed open communication across the entire country but also cut off the Confederacy from Texas, Arkansas and western Louisiana, the source of the major part of their supplies and recruits. It became the turning point of the Civil War. It was also significant that this was the first “joint” operation where the Army and the Navy coordinated their attacks.

I recently visited the Vicksburg National Military Park. This is a beautifully laid out and maintained area covering several square miles where you can walk or drive around the actual battlefields and view the graveyards and monuments to the soldiers who fought and died in the siege.

To me the most interesting artifact is the USS Cairo, (pronounced “Kayro” and named after the city in Illinois where she was built), one of only four remaining Civil War “Ironclads.” (The Ironclad was developed during the Civil War and was a method of covering the entire outside of the ship with iron armor, thus making her less vulnerable to enemy cannon fire). She was sunk in the Yazoo River behind Vicksburg by an electrically detonated mine on her maiden voyage. The Cairo lay covered with mud for over a hundred years. Now she has been salvaged and put on display in the park, with much of her original weaponry and machinery. Parts that had rotted away over the years have been restored and you can walk through her just as she was when she saw action 150 years ago.

I came away thrilled that I had experienced a part of history, but also with a great feeling of sadness because that war killed more Americans than all our other wars put together.

Photo: USS Cairo in 1863. Courtesy of the Library of Congress