When someone mentions canals, most people think of the Panama, Suez, and sometimes the Erie. Very few people have heard of the Morris Canal which traversed Northern New Jersey for about 100 years.

Back in the 1820s, the cities of New York and Philadelphia had burned up all the available timber in the area, and transportation was such that it was cheaper to buy soft coal mined in Britain and shipped 3,000 miles by sailing ship than to buy anthracite coal mined in Northern Pennsylvania and transported overland by mules.

At the time, a mule could pull about a ton and a half of cargo in a wagon, whereas the same mule could pull up to 50 tons along a tow path in a canal boat. Therefore, some New Jersey businessmen proposed building a canal connecting the Delaware River across Northern New Jersey to the Hudson River. They formed a corporation and sold shares totaling $2 million and began digging.

Unfortunately, they were working with a 75-year-old survey which put the height of the mountains they had to cross at 185 feet above sea level. It was actually closer to 1,000 feet! They had already formed the company and sold the shares, and the concept of the canal was still valid, so they decided to keep going.

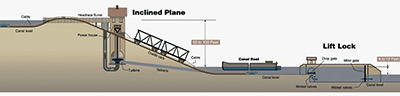

A standard canal lock can raise or lower a boat from eight to 15 feet. This canal would require hundreds of locks to get up over the mountains and back down again and need more water to operate them than was available. However, an engineer from West Point had invented an inclined plane railway which could lift and lower a canal boat up to 100 feet! It was originally powered by an overshot water wheel and later switched to the more efficient water powered turbines.

A turbine powered inclined plane boat lift.

These inclined railways would have a carriage on rails about 11 feet apart. Starting underwater in one part of the canal, where a boat would be loaded on top of the carriage. Then a cable would pull the carriage out of the water and up the rails to the higher part of the canal, where the carriage would go back underwater to allow the boat to float off and be pulled by the mules to the next inclined railway or lock.

The lock was a much simpler mechanism. It was just a section of canal with gates at each end, into which the boat would be floated and moored. Then the gates behind the boat would close, and the chamber would be filled or emptied of water until the level was the same as at the other end of the lock. Then the gates in front of the boat would open and the boat would be pulled out at the higher or lower level and continue its journey. Once they got to the highest point of the canal in Lake Hopatcong, they would reverse the process, and the boat would be pulled on to the next set of locks or railways for the descent to sea level of 914 feet. The canal also traveled through countless tunnels and across overhead aqueducts.

A series of canals already connected Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley to the Delaware River, where a cable ferry would pull the canal boats across the river to the Jersey side where they could join the new Morris Canal. This eased the transportation of fuel, raw materials, crops and finished goods between Pennsylvania and the New York area. It opened up the iron mines of Northern New Jersey as well as the coal fields of Northern Pennsylvania. It also turned the villages of Phillipsburg, NJ and Bethlehem and Easton, PA into thriving industrial towns.

Use of the canal reached its peak in the 1880s, but with the improvement of railroads, plus the development of iron ore mining in the Great Lakes region, the traffic began to fall off. By the early 1900s, the switch from coal to oil and the advancement of shipping by truck sounded the death knell for the Morris and most other canals in the country. It was officially closed in 1924.

The land still exists, and parts of the canal are still there, but much of it has been sold off and most of the infrastructure has been destroyed, including some beautiful aqueducts. A lot of it has been taken over by municipalities as green space.

The canal is listed in the National Register of Historic Places and is a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark. Waterloo Village in Sussex County, NJ is a restored canal town with an inclined plane, guard lock and a watered section of the canal. There are also period buildings and a museum.

Now let’s compare the Morris with the other canals:

The Erie Canal was built in the 1820s, about the same time as the Morris, but although it is over 500 miles long, it traverses mostly level land and has a vertical lift of 524 feet, with no mountains to traverse. Like the Morris Canal, it was privately funded.

The Panama Canal was completed in 1914, over 90 years after the Morris and the Erie. It is about 50 miles long and has a vertical lift of 85 feet. It traverses nearly impenetrable jungle, and the builders were plagued by the diseases of Malaria and Yellow Fever, carried by mosquitos, which killed over 5,600 workers. Unlike the Morris and the Erie, it was funded by federal money and had the might of the US Army Corps of Engineers to build it. As a percentage of the country’s GNP, it was comparable to putting a man on the Moon, all funded by taxpayer money. When it was built, technology had advanced, so it used powerful steam shovels and dredges to dig, railroads to remove the spoils and pneumatic drills and TNT for blasting. The Morris and Erie used men shoveling by hand, mules to carry away spoilage and star drills with sledgehammers wielded by men for drilling the holes in the rock to pack with black gunpowder for blasting.

That leaves the Suez Canal. Although it gets a lot of press, due to the politics of the region, I consider it no big deal. It’s just a big ditch at sea level. Building it simply required moving a bunch of sand. It has a slight current at the Mediterranean end and tidal changes at the southern.

In my mind, the most memorable thing about the Suez Canal is that it is responsible for getting the word “posh,” meaning “luxurious” or “first class” into the English language. Before the canal was built, ships going back and forth from England to her colonies in Asia had to go around the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa, so the journey was mostly north and south. The Suez Canal made the journey mostly west to east, meaning the southern side of the ship received the most sun during the voyage. This was in the days before air conditioning, so cabins on the southern side of the ship were sweltering during the voyage. Therefore, VIP passengers had “P.O.S.H.” stenciled on their luggage, meaning “Portside Out, Starboard Home.”

Author’s Note: As this goes to press, the SS United States, the world’s fastest Trans-Atlantic Liner has left her berth in Philadelphia and is being towed south to Florida where she will become the world’s largest artificial reef. (Refer to “On the Water,” Lakeside News November 2024)

Route of the Morris Canal from the Delaware River, through its highest point at Lake Hopatcong to the Hudson River and New York City. (Map, Canal Society of New Jersey)

Image: courtesy Canal Society of New Jersey