Editor’s Note:

Before digital photography, photos didn’t lie. Such is the case with the Booth Western Art Museum’s exhibition Dorothea Lange and Pirkle Jones:“Death of a Valley,” which tells the story of the Berryessa Valley in northern California in the final days before the opening of Monticello Dam in the 1950s. In 1956, photographers Dorothea Lange and Pirkle Jones, armed with a Life Magazine assignment, set out to document the final year of California’s Berryessa Valley before it was submerged beneath Lake Berryessa to aid in water supply and agricultural irrigation for the quickly growing state of California. Around that same time, Buford Dam/Lake Lanier was being built. Although the projects were similar, their purposes and management were diversely different.

Lake Lanier has more than exceeded expectations of its original objectives when it was authorized by Congress in 1946. Its original purposes: provide hydroelectricity, navigation, and flood control of the Chattahoochee River, and water supply for the city of Atlanta.

Except for the recently settled multi-decades-long water negotiations between Georgia, Florida and Alabama, major controversy about the lake’s construction has been minimal. Several severe droughts have plagued the lake during its six decades, but those issues are not man-made.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the country, controversy galore was brewing in Berryessa Valley, Calif., where construction had begun to build Monticello Dam that would create Lake Berryessa. Its major purposes: flood control, municipal and industrial water supply, and irrigation water supply.

Both projects were authorized by Congress, and both were completed during the 1950s. Both had flood control and water supply as their purposes. However, that’s where the similarities end.

Lake Lanier and Buford Dam were built and are still managed by the US Army Corps of Engineers under the US Department of Defense.

The construction and management of Lake Berryessa and Monticello Dam were/are the responsibility of the US Bureau of Reclamation, part of the Department of the Interior. Controversy has followed Monticello Dam and Lake Berryessa almost since the beginning.

Today the US Bureau of Reclamation serves 17 states in the western US. According to its website, the government agency refers to itself as a water management agency, the nation’s largest wholesale water supplier. It operates 294 reservoirs that supply drinking water and irrigation. In the 1970s, the dam’s powerhouse was built to produce hydropower.

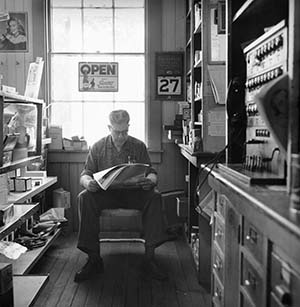

Berryessa Valley, 1956 / Photo: by Pirkle Jones

When full, the Lake Berryessa Reservoir encompasses more than 20,000 acres and has 165 miles of shoreline. But before the dam was built, the area was targeted for a water project to support agriculture and the fast-growing population of the 1930s and 1940s.

At that time irrigation was the focus of the project to help increase agricultural production through irrigation. After much debate about where and how to solve the water issue, the Bureau of Reclamation persuaded area officials to focus on Monticello Dam on Putah Creek. That meant the town of Monticello and the surrounding valley would be flooded.

Dorothea Lange, a former portrait photographer employed by the US Farm Security Administration to document the Depression, was hired by Life Magazine to capture the final year of Monticello and the Berryessa Valley in Napa County in 1956. She brought in fellow documentary photographer Pirkle Jones to collaborate.

A recent article from YourTownMonthly.com said that 250 residents of Monticello were moved out to make room for the dam and lake. About 300 graves were relocated to higher ground, and buildings were demolished.

Jones Cemetery, disinterred graves

The two photographers focused on the displaced residents of the valley for a year, capturing the faces, the landscape, the buildings and the emotion.

Black-and-white images of cemeteries and headstones, giant trees being felled to make way for construction, cowboys driving cattle across the countryside with dust flying, photographs of people in their homes, their stores and on their land, a barn burning out of control and a home being moved on a trailer to be relocated showed not only the facts of the year, they also revealed the heart, the emotions and the angst of people affected.

Photos of the final harvest, the town’s last Memorial Day, heavy machinery and government workers stripping the land and demolishing landmarks, and the valley filling with water proved to be more than simple documentary photography. As was Lange’s and Jones’ trademark, their images told the story.

When they completed their assignment, Life Magazine refused to publish their photo essay, saying the images were too unsettling. The magazine returned the rights to the photographers. However, the photographs continue to tell the story of Lake Berryessa and Monticello Dam.

In 1960 the journal Aperture published 30 of the images, titling it “Death of a Valley.” The photos were later exhibited at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Now these same photographs, plus many more, are on display at the Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville. The exhibit features more than 90 vintage black-and-white images, showing Berryessa Valley’s fate through the eyes of two legendary artists.

A barn burns in the valley. Photo: by Pirkle Jones.

A scene in the McKenzie Store. Photo: by Dorothea Lange

A woman greets a visitor to Berryessa Valley. Photo by Dorothea Lange.

Dorothea Lange poses in McKenzie Store. Photo: by Pirkle Jones

Photographer Pirkle Jones. Photo by Ansel Adams

The Booth Western Art Museum’s exhibition is produced with Atlanta’s Lumiere Gallery and the Special Collections and Archives at the University of California at Santa Cruz.

In addition to the images, the exhibition includes some of Lange’s original correspondence, including letters to Jones and a telegram from Life Magazine.

The exhibition continues through June 9. Booth Western Art Museum is located at 501 N. Museum Drive, Cartersville. Website: www.boothmuseum.org.