I was just a regular little kid involved with Little League baseball and the usual stuff but always had enjoyed hunting birds and squirrels with my Red Ryder BB gun and catching bream and an occasional bass in local ponds. For a few summers, until I was 12 or so, I went with my maternal grandmother and grandfather to visit my relatives in the mountains of north Georgia. There I fished every single day, except Sunday, with my cousin, Winifred. We all went to church on Sunday. He was a kind, gentle, mountain boy, a year older than I was, and was always willing to show the city kid about the mountains, the fish, and the other critters that live in the hollows and mountainsides. I fished with my paternal grandfather in the ponds around the countryside. I’ve probably told you and written about those trips many times. You can read about that another time.

Guess the first venture into capitalism, based on outdoor pursuits, occurred when I was 14. See if this works as a start.

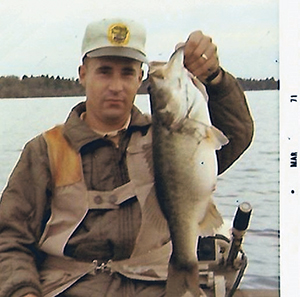

Rick holding a 6+ pound largemouth bass – March 1971

I met a fellow in the 9th grade whose name was Jeffery Merrick Hobbins, he went by “Rick.”

He was a hunter and fisherman; a good one. I guess his most valuable trait was that his father, Len Hobbins, had a boat and would let me tag along with them to Lake Lanier in the late ’50s. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s digress to Rick and O’Neill’s first commercial fishery.

In the early to mid-50s, in our area of DeKalb County, existed some of what we called “dollar” lakes; one could fish all day for a dollar fee and keep whatever you caught. These lakes were very popular, even to the extent that on holidays it was difficult to find a place along the bank to cast a bait. One set of three lakes was called “Chinchilla Lakes.” Seems the owner had an adjoining Chinchilla raising facility nearby so … . Anyway, Rick and I went there often on Saturdays and caught our share, nothing special really but we were honing our skills each time. Rick figured out that by putting a half-ounce sinker on the end of the line preceded by a rather large treble hook, about two feet above, he could cast out into the shallow upper end of the lakes where the creeks flowed in and could simply rake the hook across the muddy bottom with a jerking motion and snag one catfish after another for as long as we wanted or needed.

The fish were there because of the fresh flowing cooler current. Of course, we likely scarred up lots of poor little catfish critters without hauling them in. The lake and landowner caught us and asked us to leave and not come back. We were 14-years old and were not conservationists, so we didn’t really understand why the owner was so upset. We do now.

So, by necessity, we changed our weekly summer haunts to a place a few short miles away which, I believe, was called Parker’s Pond. Same thing: catfish and carp and lots of folks fishing on weekends and holidays. Rick and I soon figured out that lake, how to catch the fish that lived in it, and capitalism took charge.

We’d buy several cans of Green Giant whole kernel corn, or another brand since it didn’t matter, and toss handfuls out into the lake where we were fishing. A can of corn was priced at nineteen cents so the investment was tiny. The smell of all that corn soon attracted a generous portion of the carp and cats in the pond and we’d be catching them by the buckets full.

So now we thought, let’s sell these fish. We certainly can’t use them all. Ah Ha! We were in business. On a given Saturday, my mother would take us to the pond about sun rise, and we’d stake out a good spot, and load up the shallow lake bottom with corn kernels. We’d then use corn threaded on our hooks for bait. While Rick staked out our claim and fed the fish, I’d walk around the lake and invite other fishermen to visit with us before the day ended if they needed, and we’d sell to them the fish we had caught. Early in the day, I’d usually get rebuffed rather kindly as in “No sir, don’t need any help from you, I’ll catch my own” all the way to smartly replying, “I don’t need you to catch any fish for me you little punk, get away from here.”

However, before the day ended, and his mother came to pick us up as the sun began to drift and the color turned golden, we would have other fishermen standing behind us laying claim to, and offering to pay us for the next catfish or carp we landed. The fee was only $1 to fish, less than that for the corn, and we’d each pocket seven or eight dollars for a day’s fishing.

We’d cut forked sticks and line up six rods and reels, usually Zebcos or Johnson Centuries, and fan cast into the area where we’d tossed the corn, sit on our little tackle boxes or simply lie down in the dirt, use our newly found wealth to eat Moon Pies and drink Cokes all day and have profits left over. It worked. I don’t know how we could have been able to tell but we always felt we had most of the fish in the lake right in front of us by noon every day.

Capitalism at its finest. Surely did beat working all day at the local grocery store bagging groceries and making tip money.

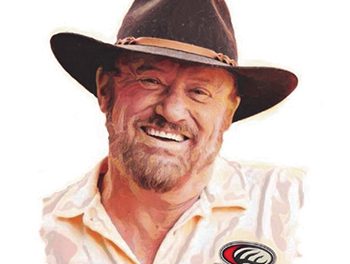

Will that serve as a starter for our careers? Rick spent most of his business life as a rep for Browning selling sporting goods all over the world and you know what I’ve done – and still do – to make ends meet so, what do you think? It’s as good a beginning as any.

During all these years, I guess you could say that Rick and I have been “selling our catch.”

Post Script:

Rick and I have been friends all these years from 14-year old fishing buddies until the present. He’s 78 and I am 77. OK.

When we entered our 30-plus years, and our fledging local bass tournament participation began to grow, we were natural but very friendly competitors.

Here goes. Rick called one day and surprised me with the notice that he had been approved to be a “field tester” for Tom Mann’s Jelly Worms, a company out of Eufaula, Ala. While I was proud for him, I was naturally jealous because I had always thought I was as good a bass fisherman as he and could also be a candidate for association with a bait company.

So, I do not remember how I did it, but I reached out to a local sporting goods sales representative company who sold Creme Worms. It turned out to be the Frank Carter Company located in the Buckhead area of Atlanta. I asked for an appointment and visited with the sales manager, a fellow named Sherman Prather, on a cold January Saturday morning. After a brief chat, he granted me AA Field Tester status. I was so proud. That was the start of a 30-year association involving a vast range of brands and products represented nationally and worldwide, by one of the most powerful and well-thought-of gentlemen in the sporting goods industry, Mr. Frank Carter. Frank and I became fast friends and, with a story I will tell later, without his help, assistance and advice, O’Neill would never have a television or eventually a radio show.

Here’s the irony in the story. As far as being a field tester for Tom Mann’s Jelly Worms, Rick was only kidding me because he knew it would make me envious. When I found out his ruse early on, I intervened on his behalf and he also was granted the status by the Carter Company as a Creme Worm AA Field Tester.

As they say, the rest is history.